Run first in Oral Health magazine. You can read the latest issue of Oral Health magazine here.

Melanie Pomphrett summarises the results from her dissertation that sought to find out the views of dental hygienists and therapists working under direct access in primary dental care settings.

Melanie Pomphrett summarises the results from her dissertation that sought to find out the views of dental hygienists and therapists working under direct access in primary dental care settings.

Last year, I completed an MSc in advanced and specialist healthcare (applied dental professional practice) at the University of Kent. My research focused on the views and experiences of dental hygienists and/or therapists working under direct access in primary dental care settings. I wanted to evaluate the impact of direct access on their working practices since its implementation in 2013.

To inform the research project, I conducted a literature review. I therefore sent a semi-structured questionnaire to BSDHT members to gather quantitative data from the target population.

This article aims to present a summary of this research and my findings.

Direct access and attitudes

The General Dental Council (GDC) introduced direct access in the UK in 2013. It allows patients to access the services of a dental hygienist and/or therapist (DHT). All without the patient seeing or needing referral from a dentist.

The British Society of Dental Hygiene and Therapy (BSDHT) and British Association of Dental Nurses (BADN) heavily supported it. But the British Dental Association (BDA) opposed it (Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray, 2013; Turner and Ross, 2015).

In two of the selected papers, dentists expressed concern, via survey responses, that DHTs working under direct access might undermine their role and threaten their positions (Coplen and Bell, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2015).

In contrast, Turner and Ross (2017) found that 86% of DHTs working under direct access referred to a dentist within their practice. Likewise, Northcott et al (2013) found no evidence of DHTs or dentists losing business because of direct access. On the contrary, they found there was the potential to increase gross revenue by up to 30% utilising DHTs in this way.

Turner and Ross (2015) found that dentists were concerned about the clinical ability of DHTs. However, 76.7% of the dentists did not train alongside DHTs and not all worked alongside them. This suggests their lack of experience working with DHTs might be the reason for their concern (Turner and Ross, 2015).

Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray (2013) did not support such concerns. They cited evidence suggesting that attitudes amongst dentists were more positive if they had direct experience of working with DHTs.

Northcott et al (2013) also advocated this. They found that working relationships between dentists and DHTs tend to be more positive when they work together.

Patient safety and satisfaction

Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray (2013) and Coplen and Bell (2015) found no evidence of increased risk to patient safety. Instead, they identified an opportunity for DHTs to provide dental services to under-served populations.

All five papers identified a lack of evidence available to suggest that direct access compromises patient safety (Northcott et al, 2013; Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray, 2013; Coplen and Bell, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2017).

Three papers recorded high levels of satisfaction and acceptability from patients regarding direct access. Turner and Ross (2017) found that 65% of respondents in their study said their patients were very favourable regarding direct access and 26% were quite favourable.

Delivery of direct access in practice

All five papers recognised the benefits of direct access to DHTs. However, they also discussed the challenges of delivering it due to certain procedures within the remit of a DHT requiring either a prescription from a dentist or a collaborative agreement with a dentist (Northcott et al, 2013; Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray, 2013; Coplen and Bell, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2017).

Each study had limitations in relation to the methodologies used in providing evidence to answer their proposed research question:

- Two studies experienced low response rates – 27% (Turner and Ross, 2015) and 48% (Turner and Ross, 2017)

- Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray (2013) conducted a rapid, systematic review of the literature. As such, risked introducing bias by potentially overlooking relevant information. The selected literature was not exhaustive, due to time constraints (Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas, 2010)

- A comprehensive search of the literature returned few studies relating to the views of DHTs working under direct access in the UK. The same author conducted the three UK studies, which could introduce some bias (Turner, Tripathee and MacGillivray, 2013; Turner and Ross, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2017), but this also reflected the paucity of research in this area

- Only two studies surveyed DHTs solely (Coplen and Bell, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2017). This gap in the literature suggested more contemporary views of DHTs would add value to the current knowledge base.

Confidence treating patients under direct access

BSDHT members, by the BSDHT administration team, conducted this new quantitative piece of research.

BSDHT members, by the BSDHT administration team, conducted this new quantitative piece of research.

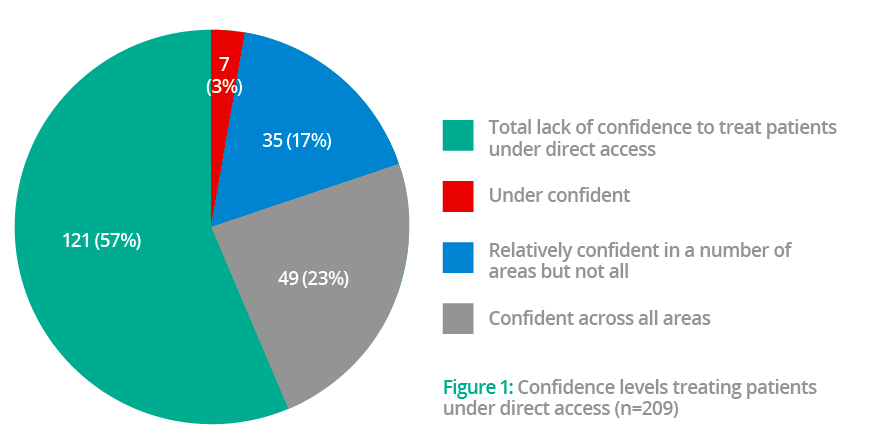

The majority of respondents (n=121; 57.89%), felt confident across all areas to treat patients under direct access. Whereas 35 (16.75%) felt under-confident, seven (3.35%) felt a total lack of confidence to treat patients under direct access, and 49 (23.44%) felt relatively confident in some areas but not all (these responses total 212, therefore some respondents have chosen more than one answer).

These areas included: soft tissue check, working without radiographs, taking medical histories, being unable to prescribe local anaesthetic and lacking confidence in providing restorative work. The respondents also expressed concerns around:

- Litigation

- Implants

- Diagnosis

- Lack of time

- Lack of nursing support

- Full base charting

- Spotting oral lesions

- Note taking

- Oral medicine.

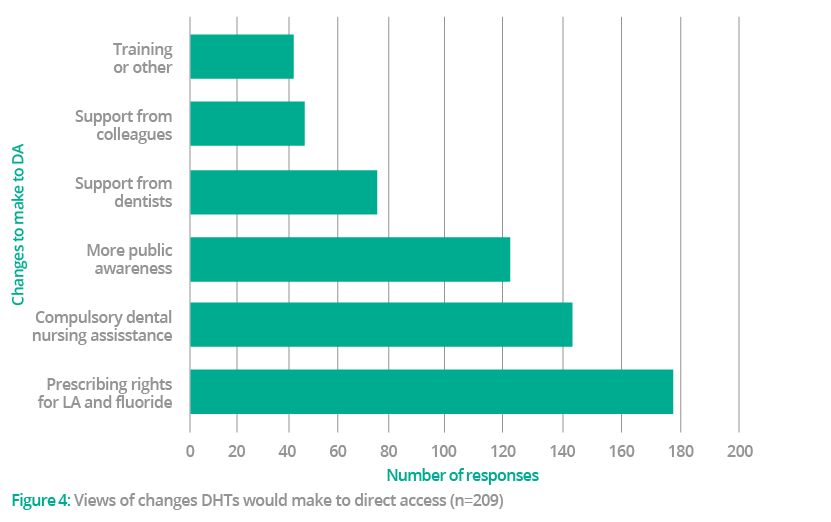

Participants were asked about changes they’d like to see. The most common response was ‘prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride’, as chosen by 176 respondents (84.21%). ‘Compulsory dental nursing assistance at all times’ was chosen by 145 (69.38%), followed by ‘more public awareness’ (n=123; 58.85%). ‘Support from dentists’ (n=74; 35.41%), ‘support from colleagues’ (n=47; 22.49%), and finally, ‘training or other’ was chosen by 42 respondents (20.10%).

Participants were asked about changes they’d like to see. The most common response was ‘prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride’, as chosen by 176 respondents (84.21%). ‘Compulsory dental nursing assistance at all times’ was chosen by 145 (69.38%), followed by ‘more public awareness’ (n=123; 58.85%). ‘Support from dentists’ (n=74; 35.41%), ‘support from colleagues’ (n=47; 22.49%), and finally, ‘training or other’ was chosen by 42 respondents (20.10%).

These respondents were invited to include written responses on changes they would make to direct access and the responses included: ‘The ability to work under direct access in [an] NHS setting’. One respondent stated that a compulsory course for DHTs, specifically for working under direct access, would increase clinicians’ confidence in allowing direct access to operate in their practice.

The most common written response mentioned the need for additional training for DHTs. Other common responses included increasing time for direct access appointments and providing more information on the treatments that can be performed under direct access.

Limitations faced under direct access

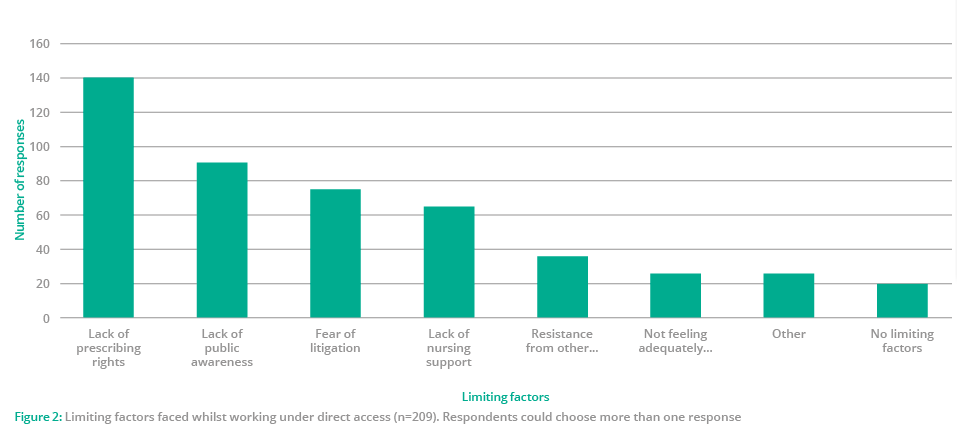

The main limiting factor faced by DHTs while working under direct access was ‘lack of prescribing rights’, as indicated by 140 participants (68.29%).

‘Resistance from other clinicians’ was chosen by 34 (16.59%), which links with the results from the question on changes that would be made to direct access – ‘prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride’ was chosen by 176 respondents (84.21%).

Only 29 (14.15%) reported ‘not feeling adequately trained’. And 42 respondents (20.10%) chose ‘training or other’ when asked what changes they would make to direct access. This suggests that, despite DHTs having self-confidence working under direct access, external factors such as lack of prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride, were limiting their scope.

Future work needed

This study highlighted areas that are currently creating limitations for DHTs working under direct access. Lack of prescribing rights was the most common limiting factor chosen by the participants. It remains an ongoing issue in working practice, both in the UK and abroad. This is despite being identified as a problem in multiple studies (Northcott et al, 2013; Coplen and Bell, 2015; Turner and Ross, 2017).

A systematic review of evidence would be required to determine if allowing DHTs to prescribe POMs within their clinical remit would pose a risk to patient safety.

The BSDHT and BADT are gathering evidence on the negative effect that these restrictions are having on DHTs in practice.

The present study indicates that the number of patients DHTs see under direct access remains low. As was also seen in a previous study by Turner and Ross (2017). Further research into the reasons behind this would be beneficial to explore how to improve direct access for patients, DHTs and potentially other DCPs.

Conclusions and recommendations

Despite many respondents reporting that the introduction of direct access has benefitted the patients they see, many limiting factors were identified within this study.

Not all DHTs were offering direct access appointments at the time of this study. But, most notably, those who were treating patients under direct access each month reported seeing low numbers. Despite feeling fully confident to practise under direct access.

Compulsory dental nursing assistance was a change that DHTs would like to see.

The common, limiting factors to direct access were lack of prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride, lack of public awareness and fear of litigation. Other commonly mentioned limiting factors also include more guidance and training on how to practise under direct access.

DHTs not having prescribing rights for local anaesthetic and fluoride, remains a considerable limitation for direct access to operate effectively. A dentist is still required if a DHT carries out treatment under local anaesthesia or applies fluoride varnish. Despite DHTs receiving training to perform these procedures.

DTs are unable to perform their full scope of practice on the NHS directly, as NHS performer numbers are only given to dentists. However, this study did not explore this topic as participants were mainly singly-qualified DHs and dual-qualified DHTs.

With dentistry moving towards the wider utilisation of DCPs and embracing skill mix to meet the needs of an ageing population with more complex dental needs. These limitations are therefore preventing DHTs from using their full set of skills.

Changes needed

The two professional bodies representing DHTs are currently working to allow the ability to add exemptions to the Medicines Act for local anaesthetic and fluoride.

A review into the current training for DHTs wishing to practise under direct access would also be beneficial to determine if more guidance is needed.

Continuing professional development (CPD) after graduation is an essential part of maintaining professional registration with the GDC. Therefore, development of a CPD course specifically for DHTs wishing to operate under direct access might help provide clarity for those who want to practise under direct access but need further guidance.

Numbers of DHTs undertaking further education at postgraduate level were low in this study. It would seem that direct access does not appear to have incentivised DHTs to take their education further.

While most DHTs feel fully supported in their practice/s to see direct access patients, many did not feel supported or were unsure. This could be contributing to the low uptake of patients seen under direct access.

DHTs considered a lack of public awareness of direct access an issue. Direct access is controversial and therefore many dentists disagreed with its implementation. As evident in a previous study by Turner and Ross (2015) and comments from the BDA.

Assistance

Due to the current limitations surrounding prescribing rights and performer numbers for DHTs, dentists maintain their ‘gatekeeper’ role in primary dental care settings. An increase in support from dentists could go some way to improving public awareness and increasing the number of patients seen under direct access.

Turner and Ross (2015) suggest more joint training at undergraduate level and within CPD. This is further endorsed by this research.

The GDC states that clinicians must work with another member of the dental team at all times, unless there are exceptional circumstances. However, this study highlighted that more than half of the DHTs working under direct access work without dental nurse assistance.

With the increased duties that DHTs can carry out, including seeing patients under direct access, leaves DHTs in an increasingly vulnerable position. Especially in the case of a medical emergency or serious complaint.

Despite having indemnity insurance, the most commonly used indemnity providers indicate they cannot defend cases where DCPs are not supported by another member of the dental team.

This, along with the additional cost of indemnity insurance for working under direct access, is likely to remain a barrier for DHTs wishing to work under the system. To overcome this, the GDC would need to provide more clarity. Particularly on whether dental nurse assistance for DHTs working under direct access is compulsory or just a recommendation. And also work with indemnifiers to ensure they fully insure DHTs.

The results also present a broader understanding of the views of other DHTs concerning direct access. They will consequently hopefully help assist the professional bodies currently working towards exemptions for the Medicines Act (1968). Additionally, this will allow DHTs to prescribe local anaesthetic and fluoride by highlighting this is currently a major barrier.

References

Coplen A, Bell K (2015) Barriers faced by expanded practice dental hygienists in Oregon. The Journal of Dental Hygiene 89(2): 91-100

Northcott A, Brocklehurst P, Jerković-Ćosić K, Reinders JJ, McDermott I, Tickle M (2013) Direct access: lessons learnt from the Netherlands. Br Dent J 215(12): 607-610

Turner S, Ross M (2015) Direct access in the UK: what do dentists really think? Br Dent J 218(11): 641-647

Turner S, Ross M (2017) Direct access: how is it working? Br Dent J 222(3): 191-197

Turner S, Tripathee S, MacGillivray S (2013) Direct access to DCPs: what are the potential risks and benefits? Br Dent J 215(11): 577-82