In this month’s Root of the Problem, Kreena Patel covers external cervical resorption, how to diagnose it and how to treat it.

In this month’s Root of the Problem, Kreena Patel covers external cervical resorption, how to diagnose it and how to treat it.

External cervical resorption is a pathological resorption.

It initiates on the external aspect of the root, immediately below the gingival epithelial attachment. It is therefore most often found in the cervical region.

The literature states that external cervical resorption is relatively uncommon.

However, many endodontists notice it is becoming a more frequent finding.

It is difficult to know if this is due to the disease becoming more prevalent or because of better diagnosis by our dental community.

Resorption initiation

The external surface of the root is surrounded by a protective layer called precementum. Damage to this layer allows resorptive cells (odontoclasts) to penetrate the root.

The portal of entrance into the root can range in size from pinpoint to a much larger defect.

Once the odontoclasts have penetrated into the root, they are able to invade dentine, enamel and cementum.

The resorptive process itself is painless, and the patient remains asymptomatic unless pupal or periodontal symptoms supervene.

Aetiology

There is a broad list of postulated aetiological factors (Heithersay et al, 1999; Mavridou et al, 2016):

- Trauma

- Orthodontics

- Parafunction

- Bleaching

- Cracks

- Dental procedures (restorative, endodontic, periodontal surgery, orthognathic surgery, oral surgery)

- Viral infections (herpes zoster)

- Transmission from cats (feline herpes virus)

- Poor oral hygiene

- Playing wind instruments

- Developmental disorders

- Frenulum tension

- Interproximal stripping

- Malocclusion

- Multifactorial.

However, in truth we still know very little about the aetiology of this process.

Resorption progression

Following the initiation phase, odontoclasts continue to invade tooth structure via small channels.

Highly vascular granulation tissue infiltrates the resorptive channels and provides a nutrient supply to the clastic cells. Resorption can progress at different rates.

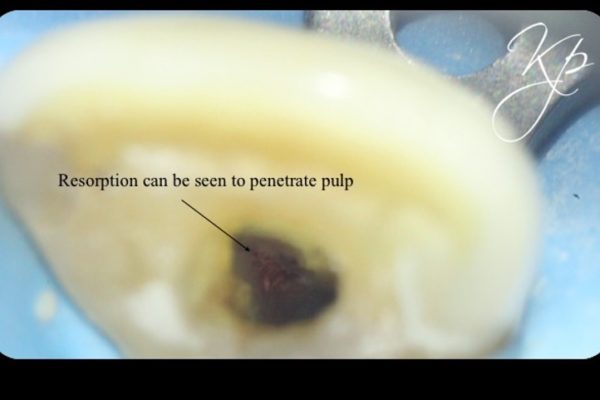

The pulp chamber and root canal are surrounded by a protective organic sheath called predentine or the pericanal resorption-resistant sheet (PRRS).

Odontoclasts find it more difficult to penetrate this layer. Therefore, often patients remain asymptomatic and the resorption remains undetected until quite a late stage in the process.

It is also the reason resorptive channels are seen progressing circumferentially around the root canal system (Figure 1).

Odontoclasts will invade around this layer and circumferentially around the root canal. As a result, the pulp can stay healthy until late in the process.

Resorption repair

Occasionally, external cervical resorption lesions can start to ‘repair’ themselves.

Mineralised (bone-like) tissue grows into the resorption, resulting in a localised fusion between tooth and the adjacent bone (Mavridou et al, 2016).

These lesions have a more mottled radiographic appearance. Resorption progression and repair may occur simultaneously.

Clinical features

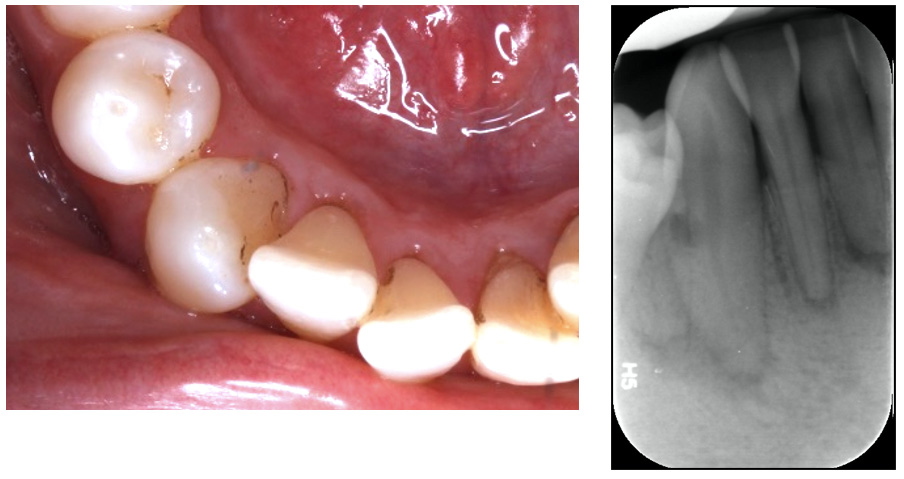

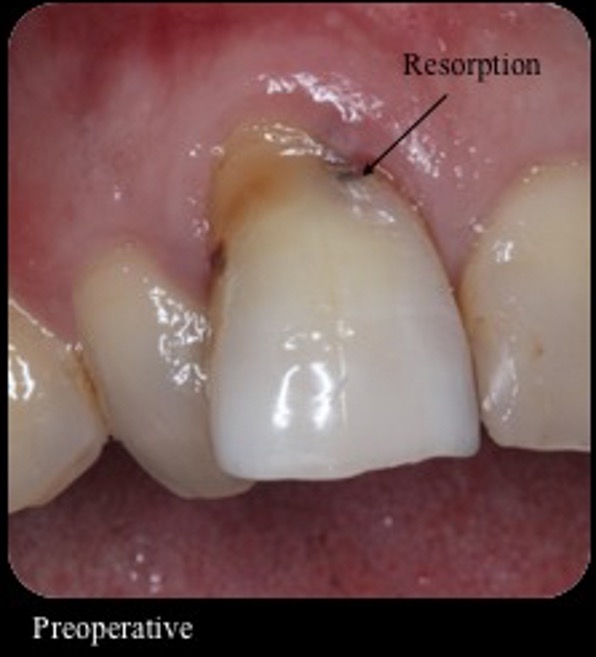

Clinical features of external cervical resorption include (Figure 2):

| Cavitation | External cervical resorption can be differentiated from caries because it is hard to probe to cavity walls |

| Irregularity in the gingival contour | |

| Pinkish discolouration of the crown | This occurs because highly vascular granulation tissue has infiltrated the lesion.

Dental hygienists are particularly well equipped at detecting these lesions. |

| Localised periodontal pocket, which bleeds on probing and can feel spongy | |

| Pain (irreversible pulpitis or apical periodontitis) | Usually a late feature.

A fine sheath (PRSS) surrounds the pulp and is resistant to resorption. |

There is an ingrowth of vascular granulation tissue into the resorption. This results in the pink appearance of the crown. Probing the tissue feels ‘spongy’ and results in profuse bleeding.

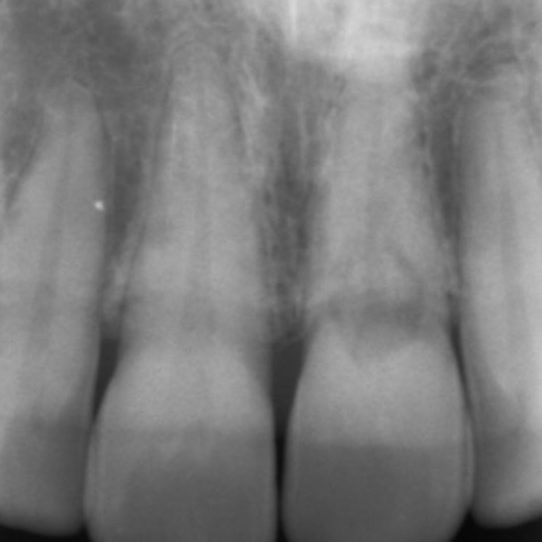

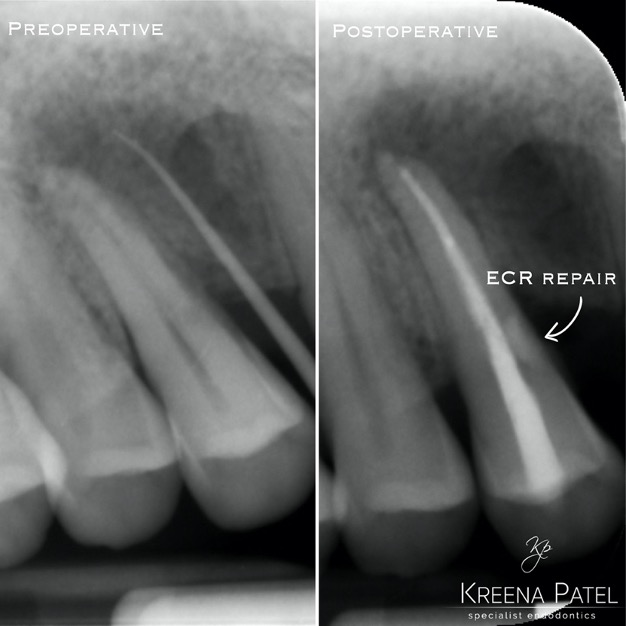

However, in many cases there are no obvious clinical signs. External cervical resorption is often detected as an incidental radiographic finding (Figure 3).

Radiographic features

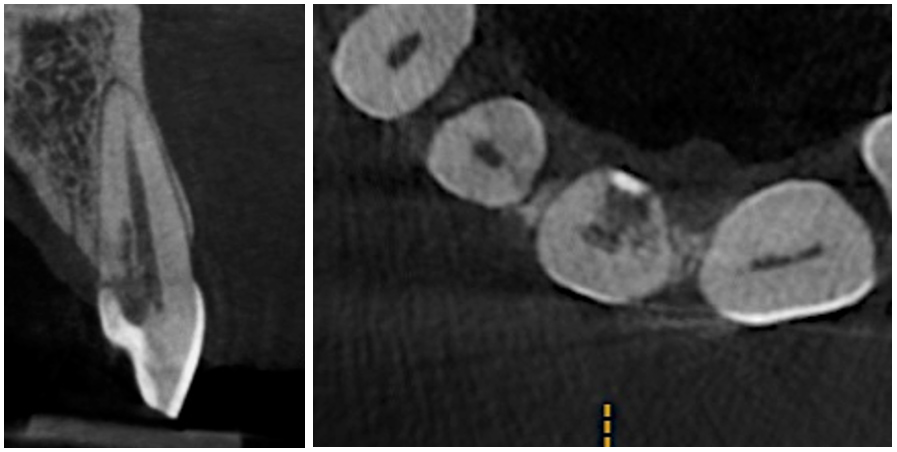

External cervical resorption typically presents as an asymmetrical radiolucency with irregular borders (Figure 4).

The outline of the root canal is visible through the lesion indicating the resorption is on the external aspect of the tooth.

The lesion may appear cloudier or mottled if it has progressed into a more reparative phase.

In my opinion CBCT is essential to assess external cervical resorption lesions prior to treatment.

I carried out a clinical study (Patel et al, 2016), which showed periapical radiographs significantly underestimated the size of lesions. They also provide limited information about the location and circumferential spread.

This results in differences in the treatment plan chosen by clinicians on how to best manage the resorption.

Parallax radiographs were also shown to provide no additional benefit.

In addition to this, not all external cervical resorption lesions follow the ‘typical’ radiographic appearance mentioned above (Figure 5). A CBCT provides crucial information to obtain successful outcome.

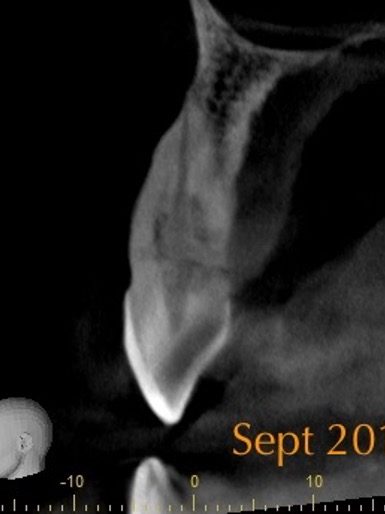

Figure 5: From the PA radiograph LR5 has the classical appearance of internal resorption.

However, the CBCT scan shows the resorption is external cervical resorption.

The resorption starts buccally at the cervical margin. It extends down the root and spreads 360º around the root canal.

We often see this appearance because the canal is surrounded by a protective predentine layer, which is more resistant to resorption

Classification

Heithersay classification

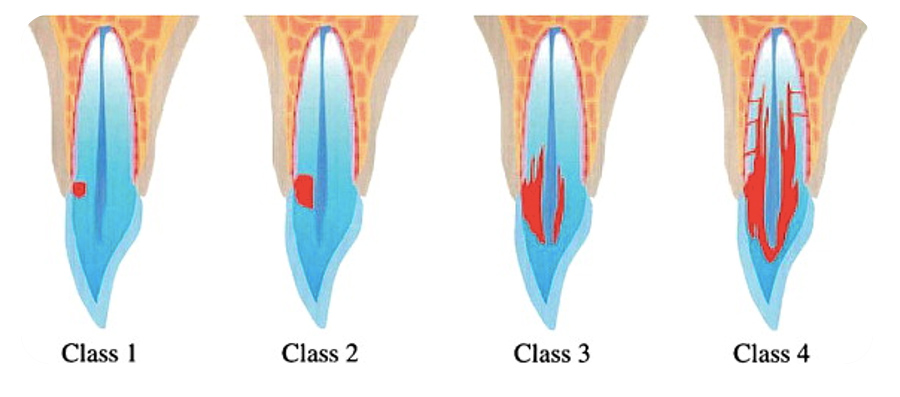

The Heithersay classification categorises external cervical resorption based on the penetration of the lesion into coronal and root dentine (Figure 6).

- Class 1: a small cervical lesion with shallow penetration into dentine

- Class 2: a well-defined lesion close to the coronal pulp, but with little or no extension into radicular dentine

- Class 3: deeper invasion of the lesion into the coronal third of the root

- Class 4: a lesion extending beyond the coronal third of the root.

However, ECR lesions spread in three planes.

We have discussed how important CBCT is for assessing and managing these cases.

A more detailed classification is now used to classify ECR in three dimensions.

3D classification of ECR (Patel et al, 2017)

ECR lesions are classified according to their height, circumferential spread and proximity to the root canal (for example: 1Bp).

ECR lesion height (coronal-apical extent):

- At CEJ level or coronal to the bone crest (supracrestal)

- Extends into the coronal third of the root and apical to the bone crest (subcrestal)

- Extends into the mid-third of the root

- Extends into the apical third of the root).

Circumferential spread:

A: ≤90°

B: ≤180°

C: ≤270°

D: >270°.

Proximity to the root canal:

d: lesion confined to dentine

p: probable pulpal involvement.

Management

Treatment involves removal of the granulation tissue and sealing the cavity. The objective is to prevent odontoclasts from continuing the resorptive process.

We carry out treatment from an external or internal approach (or a combination of both).

Accessibility to the lesion is an important consideration. Several factors will influence the treatment:

- Location: lesions that are interdental or lingual are difficult to access surgically

- Height: lesions below bone level (subcrestal) or have spread further into the root surface (3D classification 2-4) are more difficult to access surgically

- Circumferential spread: lesions spread ≤180° (3D classification B-D) are more difficult to access and repair surgically

- Proximity to the root canal: lesions penetrating the pulp will also require endodontic treatment.

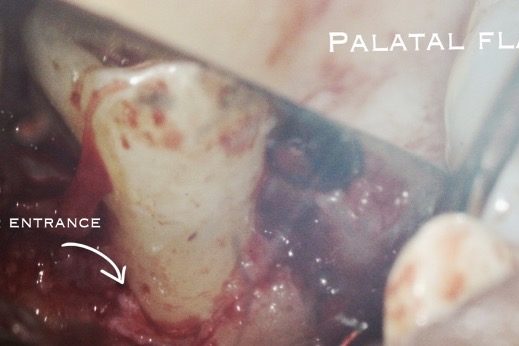

External (surgical) approach

A full thickness muco-periosteal flap is raised and ECR lesion is visualised.

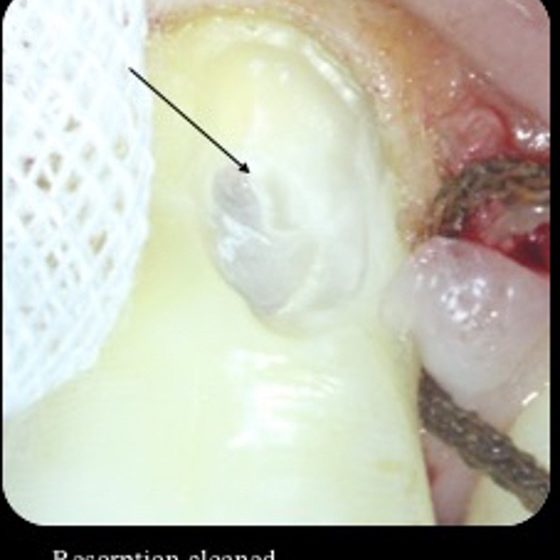

We remove the granulation tissue with a curette.

Then we use burs or ultrasonics to conservatively clean the surrounding tooth. The granulation tissue must also be removed from the surrounding bone.

We can then restore the cavity with plastic filling (Figures 7 and 8).

Various filling materials can be used; composite (Figure 9), GIC, RMGIC or biodentine.

The material choice depends on the degree of moisture control achievable, aesthetic considerations and ability for PDL reattachment.

Smaller accessible lesions fully visualised have a much more predictable and successful outcome.

As mentioned before, odontoclasts resorb tooth tissue via small channels. Sometimes these channels can sometimes communicate with the external surface of the root more apically.

If we don’t fully debride and seal, the lesion can reoccur. This highlights the importance of a recent high quality preoperative CBCT scan to assess ECR prior to treatment.

This case highlights how difficult it is to make an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan without CBCT. Figure 7a: The patient developed a buccal sinus, which was traced to UR4. The UR4 was unrestored and did not respond to sensibility testing. There were no obvious signs of resorption present on the periapical radiograph. CBCT revealed a small palatal ECR lesion which had invaded the pulp.

Internal approach

Remove the resorptive tissue is removed during root canal treatment.

This approach is often employed for lesions that are not accessible through an external approach.

However, it is more difficult to fully visualise the lesion resulting in a higher risk of reoccurrence.

Biodentine is a good material choice to seal lesions internally. It has excellent sealing ability, results in an alkaline environment, which is conducive to osteoblastic activity. It also releases calcium and hydroxide ions that favour the remineralisation process (Baranwal et al, 2016).

Other approaches

Intentional replantation (you can view a demonstration of this technique at Patel et al, 2016) and orthodontic extrusion can also be employed for inaccessible lesions.

Monitoring

ECR is often detected at a late stage and not amenable to treatment. There is an option to monitor these lesions until the tooth becomes symptomatic or fractures.

Some lesions are aggressive and progress quickly, whilst others progress slowly or stay stable for many years (Figure 10).

It is important to regularly review the lesion clinically and radiographically at yearly intervals.

Occasionally there is resorption of the alveolar bone adjacent to the lesion. This can compromise the placement of an implant later, particularly if this involves the buccal plate.

Conclusion

External cervical resorption appears to be becoming a more frequent finding.

Therefore, it is important for general dentists to be aware of the clinical and radiographic signs for early and accurate diagnosis.

CBCT is an invaluable diagnostic aid and clinicians should consider it prior to treating these cases.

We can treat ECR from an external or internal approach. Lesions not amenable to treatment can be monitored clinically and radiographically until they become problematic.

References

Baranwal AK (2016) Management of external invasive cervical resorption of tooth with Biodentine: A case report. J Conserv Dent 19(3): 296-9

Mavridou AM, Hauben E, Wevers M, Schepers E, Bergmans L and Lambrechts P (2016) Understanding external cervical resorption in vital teeth. J Endod 42(12): 1737-51

Patel K, Foschi F, Pop I, Patel S and Mannocci F (2016) The use of intentional replantation to repair an external cervical resorptive lesion not amenable to conventional surgical repair. Prim Dent J 5(2): 78-83

Patel K, Mannocci F and Patel S (2016) The assessment and management of external cervical resorption with periapical radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography: a clinical study. J Endod 42(10): 1435-40

Patel S, Foschi F, Condon R, Pimentel T and Bhuva B (2018) External cervical resorption: part 2 – management. Int Endod J 51(11): 1224-38

Patel S, Foschi F, Mannocci F and Patel K (2018) External cervical resorption: a three-dimensional classification. Int Endod J 51(2): 206-14

Patel S, Kanagasingam S and Pitt Ford T (2009) External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod 35(5): 616-25