David Gillam will provide guidance on how to diagnose dentine hypersensitivity in clinical practice.

David Gillam will provide guidance on how to diagnose dentine hypersensitivity in clinical practice.

To find out ways to treat dentine hypersensitivity, simply visit Colgate’s new microsite: colgate.dentistry.co.uk.

Dentine hypersensitivity (DH) is a relatively common, yet troublesome clinical condition. It may have an impact on the quality of life (QoL) of individuals who suffer from it.

The pain associated with the condition we describe as rapid on onset, sharp in character and transient in its duration.

Several surveys indicate that clinicians may struggle to identify patients with dentine hypersensitivity. This may in turn lead to the underestimation of the true prevalence of the condition.

Furthermore, there is some evidence that would suggest that clinicians’ lack of confidence in both the diagnosis and management of the condition.

Diagnosing dentine hypersensitivity

The classic definition of DH as described by Martin Addy was based on ‘pain derived from exposed dentine in response to chemical, thermal tactile or osmotic stimuli, which cannot be explained as arising from any other dental defect or disease’.

The wording of this definition should therefore alert the clinician to note that according to this definition DH is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, which indicates that a thorough clinical examination together with a medical and dental history of the patient should enable the clinician to come to a correct diagnosis.

Although we use the term dentine hypersensitivity, we should acknowledge the pain associated with the condition is considered an exaggerated response of the normal pulp-dentine. The patient is aware of the problem when an external stimulus, such as cold, is applied to the exposed dentine surface.

This discomfort is transient. As such it will no longer affect the patient once you remove it.

The clinical diagnosis of orofacial pain in general is both time consuming and difficult for several reasons:

- The difficulty in identifying areas of the mouth that may cause the problem and

- The highly subjective nature of pain and its variability between patients.

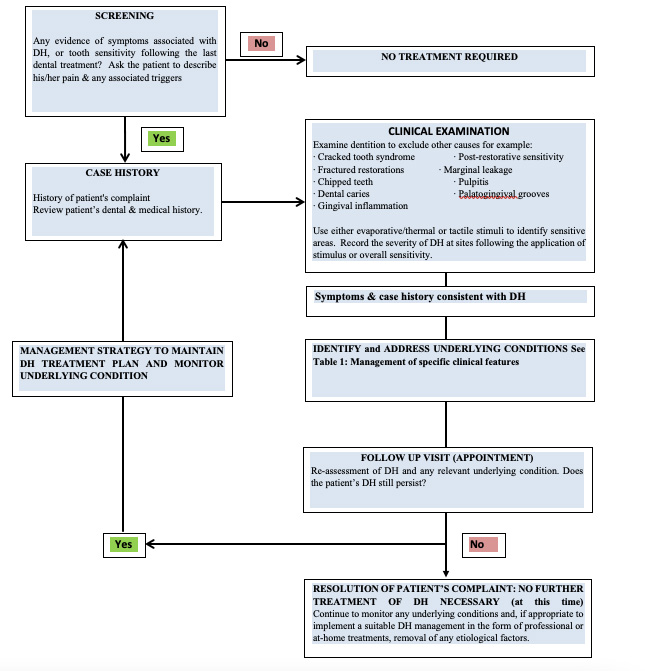

It is therefore important for clinicians to correctly identify patients with DH by excluding any confounding factors from other orofacial pain conditions prior to the successful management of the condition (Figure 1).

The problem facing clinicians

The question that needs addressing is what is the actual prevalence of DH and how does it affect the QoL? Do we underestimate or overestimate?

The answer is based on how we obtain the information on prevalence.

For example, questionnaire studies may tend to overestimate the number of individuals. Whereas if the prevalence studies were conducted in hospital or specialist-based communities, are these results the same as those obtained in general clinical practice?

The prevalence rates in the published literature would, however, indicate that, when clinically examined, the prevalence of DH is much lower than those recorded by questionnaires. Particularly in general practice.

Several factors are responsible for this:

- DH may be a relatively minor problem for the majority of the population. The discomfort individuals experience they describe as transient (episodic) in nature. Individuals either do not self-treat or compensate by changing their habits (eg drinking on the other side of the mouth). Or patients fail to report the problem when seeing a clinician

- Clinicians may not examine or screen for DH unless the patient actually complains about the problem.

The number of patients that clinicians may expect to see may also vary depending on the type of practice. But from the analysis of the prevalence studies, the overall estimate is around 10% depending on their practice environment.

Initial clinical examination

Normally the clinician would obtain a thorough medical and dental history from the patient. Here they will gather all relevant information prior to formulating an initial diagnosis.

Some relevant questions include asking if the patient has any pain. If so, how long for? Can they identify where it is in the mouth? What initiates the pain and how long does it last?

Follow up questions may include whether the pain affects their QoL. If so, how severe is the impact on their lifestyle and does anything relieve the discomfort?

A useful, yet simple, way of assessing the severity of pain and its impact is to use a numerical scoring scale (0-10) or a mild/moderate/severe verbal scale.

You can record the results in the clinical notes and review them over the course of treatment to determine whether you’re successfully managing the condition.

It is also important to consider taking a diet history to identify whether the patient has an excessive intake of acid food and drink (eg citrus juices and fruits, carbonated drinks, wines or ciders). As well as considering evidence of gastric reflux and eating disorders prior to formulating a treatment plan.

Generally speaking, patients who complain of DH will respond to cold drinks and food rather than touch, heat etc. As such it seems reasonable to use cold air from a dental air syringe (triple syringe) as a stimulus to determine whether a patient is suffering from DH.

The use of an explorer probe (drawn systematically across the exposed dentine surface in a horizontal direction) may also work. Although cold is the more ‘aggressive’ stimulus.

This will enable the clinician to identify any susceptible sites within the oral cavity.

Other confounding conditions with symptoms comparable to DH may complicate making any definitive decision at this stage.

Clinical features of DH

Traditionally we link DH to individuals with relatively clean mouths. Although the term root sensitivity or root dentine hypersensitivity (RDH) describes tooth sensitivity arising from periodontal disease and its treatment.

More recently, several investigators suggest that DH is a toothwear phenomenon characterised predominantly by erosion. This may subsequently expose the dentine surface and initiate the tooth wear lesions (including non-carious cervical lesions [NNCL], incisal/occlusal wear and gingival recession).

There appears two specific biological processes in the development of DH. Namely:

- Lesion localisation

- Lesion initiation associated with the aetiological and/or predisposing factors.

This would suggest that the dentine was initially exposed due to the loss of enamel and/or soft tissue loss associated with gingival recession (including the loss of cementum). Once exposed, the open dentine tubules become accessible to the oral environment (erosion is the key factor in lesion initiation).

As a consequence, any subsequent stimuli (eg cold) may initiate minute fluid movement within the dentine tubules. Thereby activating the mechanoreceptors in the inner third of dentine. This is the basis of the hydrodynamic theory.

Factors associated with dentine hypersensitivity

The most commonly associated teeth with DH are canines, premolars and molars. With the buccal cervical aspect of these tooth frequently exposed. This is the result of several aetiological and predisposing factors such as abrasion, abfraction, erosion, gingival recession, quality of the buccal bone, periodontal disease and its treatment, surgical and restorative procedures and patient destructive habits. (Table 1).

The clinician at this stage of the clinical examination may also record the dental caries/periodontal status (caries status, use of periodontal indices: probing depths, measure the degree of gingival recession), and any evidence of toothwear.

| Hard tissue loss eg enamel loss, denudation of cementum toothwear (attrition, abrasion, erosion [intrinsic and extrinsic], abfraction). |

| Gingival recession resulting from over excessive, inappropriate tooth brushing in plaque-free mouths, non-surgical and surgical periodontal treatment, restorative treatment. |

| Anatomical recession, thinning, fenestration, absent buccal alveolar bone plate, tooth, malposition. |

| Soft tissue loss such as the stripping of the gingiva from a finger nail or other implement (inappropriate use of interdental aids, overzealous incorrect brushing techniques). |

Table 1 Aetiological and pre-disposing factors associated with DH

Definitive diagnosis of DH in general dental practice

The process making a definitive diagnosis is a complex and time consuming one. There is evidence from surveys that clinicians do not always consider a differential diagnosis.

It is therefore important for the clinician to recognise that in comparison with other dental conditions (eg irreversible pulpitis, dental abscess, sinusitis, periodontal disease, pericoronitis, idiopathic oral facial pain) DH is relatively less common. As such it is essential to exclude all other oral conditions with a similar presentation to that of DH before undertaking any treatment (Table 2).

Patients may also experience pain from recent dental procedures (post-operative sensitivity), such as sensitivity from restorative materials, tooth whitening and bleaching as well as from periodontal procedures such as non-surgical and surgical procedures. In such cases the clinician should quickly identify the initiating cause by referring to the patient’s notes and asking the patient for supplementary information.

Aetiology |

Pain character and timing | Pain intensity | Proving factors | Relieving factors | Associated features |

| Dentine hypersensitivity

|

Sharp, stabbing, stimulation evoked | Mild to moderate | Thermal, tactile, chemical, osmotic | Removal of the stimulus | Attrition, erosion, abrasion, abfraction |

| Atypical odontalgia

(persistent dentoalveolar pain)

|

Continuous, nonparoxysmal, dull, aching and throbbing but occasionally sharp | Mild to moderate | Touch, heat and cold | Sleep and rest

Topical agents: lidocaine, capsaicin. Systemic agents: antidepressants |

May have no obvious clinical features |

| Reversible pulpitis | Sharp, stimulation evoked | Mild to moderate | Hot, cold, sweet | Removal of the stimulus | Caries, restorations |

| Irreversible pulpitis | Sharp, throbbing, intermittent/continuous | Severe | Hot, chewing, lying flat | Cold in the late stages | Deep caries |

| Cracked tooth syndrome | Sharp intermittent | Moderate to severe | Biting, ‘rebound pain’ | Trauma, parafunction | |

| Periapical periodontitis | Deep, continuous boring | Moderate to severe | Biting | Removal of trauma | Periapical redness, swelling, mobility |

| Lateral periodontal abscess | Deep continuous aching | Moderate to severe | Biting | Deep pockets redness and swelling | |

| Pericoronitis | Continuous | Moderate to severe | Biting | Removal of trauma | Fever, malaise, imprint of upper tooth |

| Dry socket (acute alveolar osteitis) | Continuous four to five days post extraction | Moderate to severe | Irrigation | Loss of clot, exposed bone |

Table 2: Differential diagnosis of dental pain (modified acknowledgement, Aghabeigi, 2002)

Aiding the diagnosis

Special investigations may, however, aid the diagnostic process. Particularly when there is confusion regarding the initial cause of the discomfort.

These may include the evaluation of pulp vitality [sensibility] testing evaluation with a pulp tester, ice stick, endo-frost, percussion, diagnostic radiographs etc.

Other conditions that clinicians can investigate include:

- Caries and teeth identified with cracked tooth syndrome (CTS) using optical illumination (fibre-optic transillumination [FOTI] with or without magnification and transillumination using a dental mirror)

- Orofacial pain conditions such as chronic idiopathic facial pain (atypical odontalgia and atypical facial pain). Chronic idiopathic pain may, however, be very difficult to diagnose as patients complaining of this type of pain often present with no obvious dental diagnosis or identifiable pathology. We recommend that these patients should refer to a specialist hospital (oral medicine clinics).

For most of the other orofacial pain conditions, the clinician can treat these based on the relevant information collected from results of the clinical and radiographic investigations as well as the recorded medical and dental histories.

Example

For example, you can identify DH and CTS in the following manner:

- Initially blow cold air from a dental air syringe on the exposed dentine surface. Then either apply a varnish or a prophylaxis polishing paste and then repeat the air blast test. The use of 0-10 VAS score prior to and following the test may give an indication as to whether DH is responsible

- A Fractfinder (Denbur, Oak Brook, IL, USA) or a Tooth Slooth II (Professional Results Inc, Laguna Niguel, CA, USA) can diagnose CTS. Although clinicians can substitute the use of a disposable plastic tip (from the triple air syringe). The presence or absence of the ‘rebound effect’ we consider a diagnostic feature of CTS.

The main features of the various conditions – together with a description of the main features – that may help distinguish between these conditions, enabling the clinician to make a definite diagnosis of DH, is summarised in Table 2.

Concluding remarks

DH is an enigmatic condition, which can have an impact on the patient’s QoL. We often overlook it in clinical practice unless the patient indicates that they suffer from it.

It is therefore important for the clinician to determine whether the patient is suffering from the condition. They can do this by taking a thorough medical and dental history (including a dietary analysis). Together with a clinical investigation to provide a definitive diagnosis.

By following the guidance in this article, the clinician should be able to make the initial steps towards a successful management of DH.

Key points

- Ask the patient if they have a history of DH

- Ask the patient if it is a current problem

- Does it impact on their quality of life? If yes ask them to elaborate on the extent and severity of the problem

- Examine the patient for DH. Particularly the buccal cervical surfaces of any standing teeth using a probe and an air-blast from a dental triple syringe

- A good history of the complaint is important. Listen to the patient and examine areas where the dentine is exposed. Identify any aetiological and predisposing factors. Listen to the patient – they will give you the diagnosis

- It is important for the clinician to recognise that the definition of DH is basically a diagnosis of exclusion. As such it encourages the clinician to exclude other potential causes for the patient’s pain (see section on differential diagnosis).

Acknowledgements

Gillam D and Koyi B (2019) Dentin Hypersensitivity in Clinical Practice. JP Medical ISBN: 1909836478

Gillam DG, Chesters RK, Attrill DC, Brunton P, Slater M, Strand P, Whelton H and Bartlett D (2013) Dentine Hypersensitivity – Guidelines for the Management of a Common Oral Health Problem. Dental Update 40: 514-24

For more information about dentine hypersensitivity, simply visit Colgate’s new microsite: colgate.dentistry.co.uk.