Abbad Toma explains how to identify potential complications before going ahead with dental implant surgery, plus how to manage and avoid them.

In my last article, I introduced the role of the rhinologist (ENT surgeon) in collaborating with the dental surgeon to best manage dental implant patients.

In this article I will discuss how to best manage sinus complications should this happen with the aim of implant preservation.

It is well established in the literature and in practice that a CBCT (cone beam computed tomography) scan or a formal CT scan of the proposed operative area, including the adjacent paranasal sinuses, is essential as part of the planning for dental implant surgery. Based on your planning, the dental surgeon decides on what implants are needed and whether this can be inserted directly or are other procedures required such as a sinus lift or zygoma implants.

Pre-implant assessment

Prior to any such surgery, the maxillary sinuses need to be assessed carefully, starting with the patient’s history including any previous sinus operations and noting any abnormalities on the CBCT. If abnormalities are seen on the CBCT, these need to be resolved before embarking on the implant surgery.

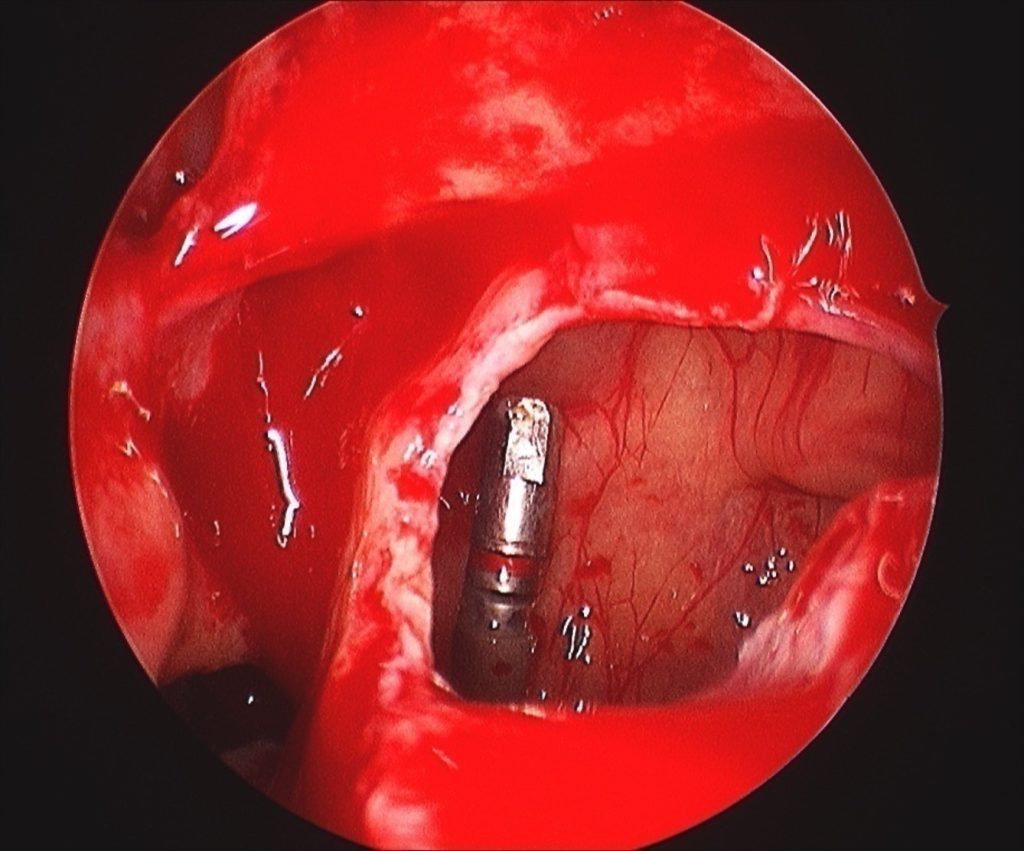

In Figure 1, the alveolar margin was too thin and the implant broke through the bone resulting in the implant falling into the maxillary sinus. This was retrieved by endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) and the oro-antral fistula repaired.

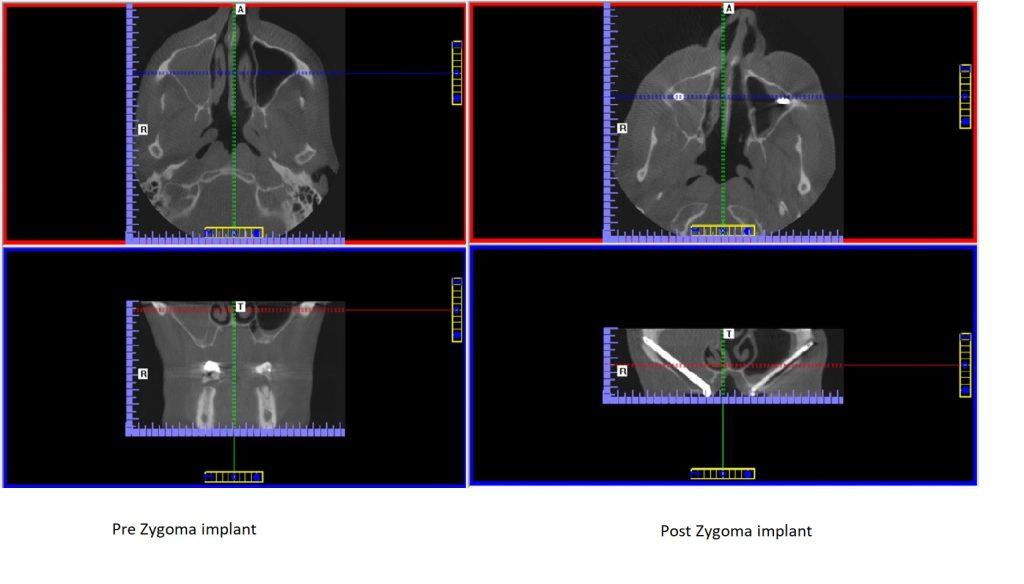

In Figure 2 the maxillary sinus is opaque (infected) due to chronic sinusitis before surgery. This resulted in infection of the zygoma implant and the patient presented with pus discharging through the skin over the zygoma area. The zygoma implant is described as running between the sinus bone and its mucosa, however when this area is infected, a drainage route is created when the bone is perforated and the sinus mucosa is infected and fragile. In this case the infection was drained by FESS and once sinus ventilation was re-established, the infection settled and we managed to preserve the zygoma implant.

Implant preservation

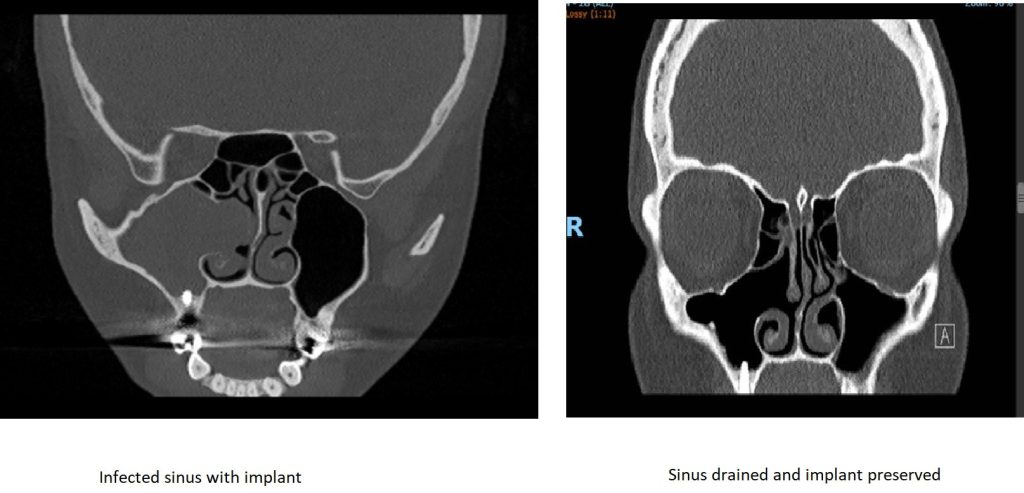

Figure 3 is a good example of implant preservation. This patient presented with psudomonas infection of the right maxillary sinus endangering the viability of the dental implant. The infection was drained by FESS and a few months later the patient had a repeat scan which showed complete resolution of the infection, ventilation of the maxillary sinus and the implant intact and secure.

Previously the assumption was that once the area around the implant is infected, the implant should be removed. However our current thinking is that as long as the implant is secure and integrated with no pain and is not loose, we should try our best to treat the infection and attempt to preserve the implant. This is particularly important with zygoma implants. To my knowledge they are very difficult to remove and therefore treating the sinuses before insertion of the implant is important, however should the area become infected but the implant is stable, we should try and preserve it.

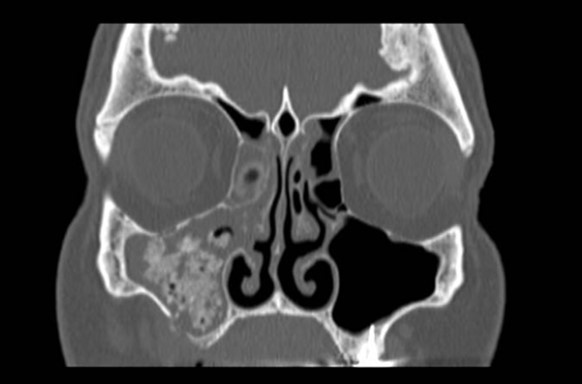

The other challenge is if sinus lift material (eg, bovine bone) escapes into the maxillary sinus through a tear in the sinus mucosa at the time of surgery or later resulting in a sinus infection, or in the case of autologous bone (favoured by maxilla-facial surgeons) and irradiated cadaveric bone used for the sinus lifts. These situations cause a severe sinus infection presenting with infected nasal discharge which can be foul smelling, pain and implant failure. Some patients present with graft material exiting through the nose.

Resolving issues

In such cases a full sinus washout through the nose (FESS) is required. All implant material needs to be removed. In some cases this procedure may need to be repeated until all graft material has been removed. Some surgeons may advocate a sublabial approach, however in my opinion, you will gain better access to remove the material especially if autologous bone blocks have been used (Figure 4).

Accessing the maxillary sinus by the sublabial route may jeopardise further sublabial surgery in this area in the future due to scar and altered anatomy, while an endonasal approach (FESS) does not interfere with the sublabial area.

Thankfully sinus complications of dental implants are rare and most of the cases can be successfully treated. Careful preoperative preparation reduces the risk even further. As an ENT surgeon I have devoted my whole consultant career to improve the management of sinus disease, along with extensive experience, both clinically and in education, I am always happy to advise and be involved in the management of such cases.

To learn more about Dr Toma, visit www.drtoma.co.uk.

This article is sponsored by Salnose.